Ford Pinto Explosions: When Profits Mattered More Than Lives

Published On 15/12/2024, 9:11:22 pm Author Zeeshan Ali AqudusThe Ford Pinto became infamous for deadly gas tank explosions, exposing how Ford prioritized profits over safety. Discover the shocking story of negligence that cost countless lives.

Today in India, car buyers are prioritizing safety more than ever. It’s a standard expectation that cars under 10 lakh should come with features like six airbags, ABS, and solid crash protection. In a market where safety has become a major selling point, it’s hard to imagine a time when the very idea of vehicle safety was dismissed in favor of saving a few dollars. But such a time existed, and it brought to light the darkest sides of corporate capitalism. One of the most notorious examples of this is the Ford Pinto.

By no means am I trying to question Ford here. Instead, I am questioning the type of capitalism that blinded decision-makers so thoroughly that even human lives stopped mattering.

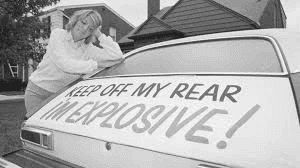

In the 1970s, Ford released the Pinto—a compact car designed to be affordable for the average American consumer. However, what was marketed as a budget-friendly vehicle became a symbol of corporate negligence and moral bankruptcy when it was discovered that the car had a fatal design flaw. The Pinto’s gas tank was placed in such a way that in the event of a rear-end collision, the fuel tank would explode, leading to horrific fires and fatalities. It wasn’t just one or two incidents; the Pinto explosions caused the deaths of at least 27 people, with many more suffering serious injuries.

Yet, Ford’s response to this crisis was nothing short of appalling. Rather than addressing the design flaw by recalling the car or making safety improvements, Ford took a calculated approach that put profits over people’s lives. Internal documents later revealed that Ford had conducted a cost-benefit analysis, weighing the cost of recalling the cars against the cost of paying off lawsuits resulting from the explosions. The company determined that it would be cheaper to settle lawsuits than to fix the problem.

This is where Ford’s ruthless capitalistic mindset truly shone through. Instead of prioritizing human life and safety, Ford chose a path of minimal expenditure. The company did not issue a recall; instead, it introduced an insurance policy for Pinto owners. The company’s actions were an embarrassing display of corporate greed, where the cost of lives was less significant than the cost of doing the right thing.

It wasn’t until the public outrage grew and legal action was taken that Ford faced any real consequences. The company eventually was dragged to court, but by then, the damage had already been done. Ford’s lack of accountability highlighted a toxic culture of cutting corners for the sake of profits, even when it risked lives.

The Ford Pinto scandal is a prime example of how unchecked corporate greed can lead to disastrous consequences. In the pursuit of maximizing profits, Ford—and by extension, corporate capitalism of that era—lost the ability to make conscious, ethical decisions. The focus shifted entirely to the bottom line, sidelining the moral responsibility of safeguarding human lives. This approach not only led to tragic losses but also permanently stained the brand’s reputation, serving as a grim reminder of what happens when companies neglect ethics in decision-making.

However, lessons from such failures have paved the way for a shift in how corporations approach product development and business strategies. Concepts like conscious capitalism and human-centered design have emerged to address these gaps. Conscious capitalism emphasizes balancing profitability with social and environmental responsibility, ensuring that businesses serve all stakeholders, not just shareholders. For the automotive industry, this approach means creating safer, more user-focused products that enhance lives rather than endanger them.

Today, safety is a non-negotiable feature in automotive design. Manufacturers prioritize advanced safety systems like airbags, anti-lock braking systems (ABS), and electronic stability control (ESC). Human-centered design ensures that safety isn’t just about surviving crashes but also about preventing them altogether. Ergonomics has become central to this vision, offering intuitive controls, enhanced visibility, and reduced driver fatigue to minimize errors.